“Movies are entertainment not history. But they reflect history. They amplify history. But some of our history is not taught or well-known. Consequently, some history is omitted from popular cinema.” Mia Mask

INTRODUCING BLACK RODEO on 10 February will see season curator Mia Mask joined by special guests for a discussion about African American westerns, their rich cinematic history and their visual culture, with an illustrated presentation tracing the evolution of Black westerns and the African American western hero. Mask will be joined by academic Clive Chijioke Nwonka for a conversation about key films, actors and themes present in the season, hosted by film and TV journalist Ellen E Jones.

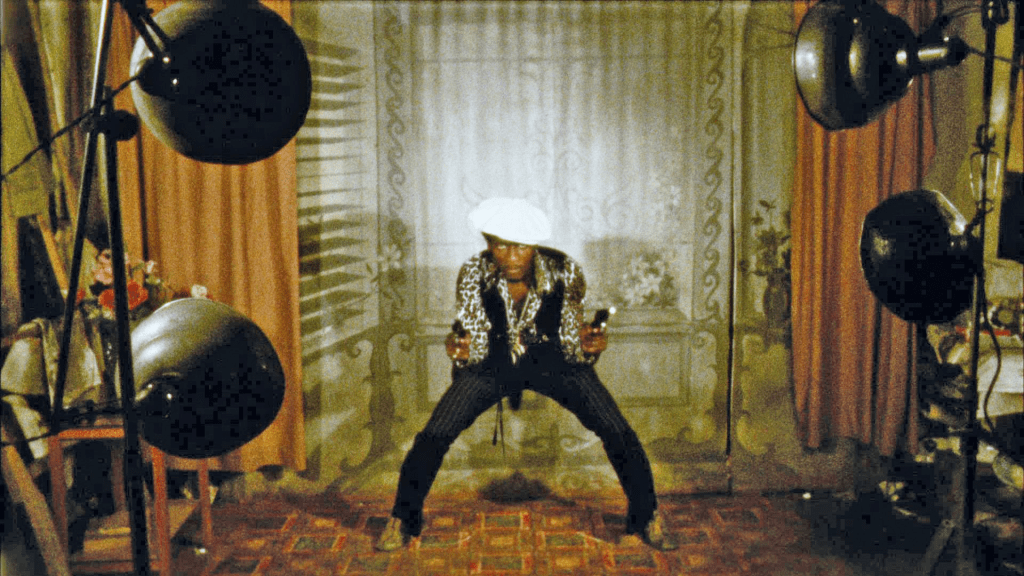

From 1 February – 18 March will be BLACK RODEO: A HISTORY OF THE AFRICAN AMERICAN WESTERN. Black westerns boldly reimagined the myths of frontier culture, blending progressive themes, campy characters and anti-establishment flair. ALT’s Editor Joy Coker interviewed Mia regarding the upcoming season and her history as scholar researching African American westerns, and how they served to addressed the “omission” of black representation in westerns.

ALT: How did you became interested in Black Rodeo, via the Book?

MM: Back in 2010, I attended the “Sidney Poitier International Conference and Film Festival.” At that conference, I was presenting on a film titled Buck in the Preacher. It was directed by Sidney Poitier and released in 1972. My work on that film led me to pursue black westerns and to find a range of African American themed westerns. I defined these as films in which the main characters are African American, and the subject deals explicitly with Exodusters and late 19th century American settler colonial history. These films had several themes in common in addition to their shared status as western genre films. They were also engaged in the project of reimagining American history by filling in the omissions with fact and fantasy. These movies were a curious lot. Some were serious, some were comical, some were campy, some were rather violent. But all of them had common ground.

ALT: Tell us about the project at the Black Rodeo, BFI how did that come about?

MM: My work on Buck in the Preacher led me to research other African American westerns. Several such films existed. Along this process many people said to me: “Black westerns?… That sounds like an oxymoron.” Or they would ask:

“There are black westerns?” Which led me to realize that few people knew about these films or the stories they reflect. I was pleased to discover that there are many such stories and figures. My book covers a subset of these movies.

ALT: How would you describe the absence of black cowboys in films?

MM: The absence of black cowboys in films is result of the absence of African American history in our curriculum, in our collective consciousness. American cinema has an indexical relationship to actual history. All films take creative license with historical facts. Movies are entertainment not history. But they reflect history. They amplify history. But some of our history is not taught or well-known. Consequently, some history is omitted from popular cinema.

When you look at American cinema broadly, you see an absence of African American history. Many of the heroic figures upon which films would be based are consequently absent from the movies. But that’s not specific to African Americans. Many marginalized groups have experienced this exclusion. For example, Mexican Americans and Asian Americans have also been excluded. The exclusion of the African American cowboy or black cowboys from movies is a function of their exclusion from American history.

ALT: What happened to the all Black Westerns of the 1930’s what are some of the titles you can mention?

MM: The all-black westerns of the 1930s did well commercially at the time of their release. Julia Lydia has written about this. Michael Johnson and others have written about these movies. These include films like Harlem Rides the Range (1939) or Two Gun Man from Harlem (1938) or Bronze Buckaroo (1939). Some of these films still exist and are watchable. You can catch them at film festivals and at retrospectives. Criterion streams them sometimes. But the industry out of which they emerged (a small, parallel, cottage industry of black-cast film production) began to see its financial decline with the transition to sound as filmmaking became more expensive and smaller, independent, low budget studios had a harder time competing with bigger studio filmmaking.

ALT: Can you elaborate on your view that African American cinema needs more attention, does that still stand today?

MM: Yes, African American cinema needs more attention. Even though there are many wonderful directors and film, stars and writers working today, it’s tough. In production, African American films still face an uphill battle. Studio executives continue to be risk-adverse investors when it comes to African American movies and any motion pictures that are not mainstream blockbusters featuring white, male action stars. Don’t take my word for it. Read Monica Ndounou’s book: Shaping the Future of African American Film: Color-Coded Economics, and The Story Behind the Numbers in which she discusses the “Ulmer Scale.” Its eye-opening.

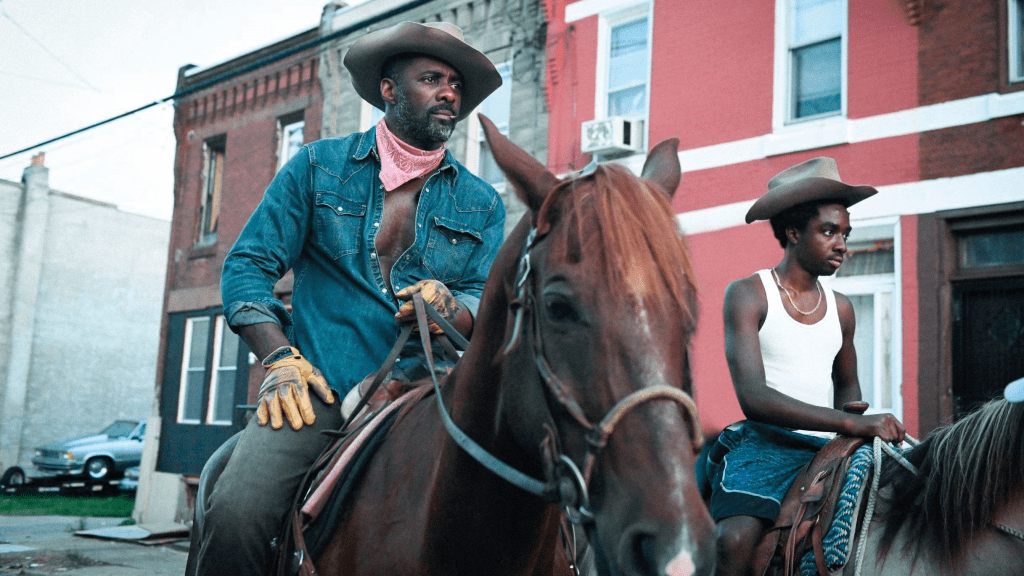

ALT: What can we expect from the programme at the BFI, why should audience engage?

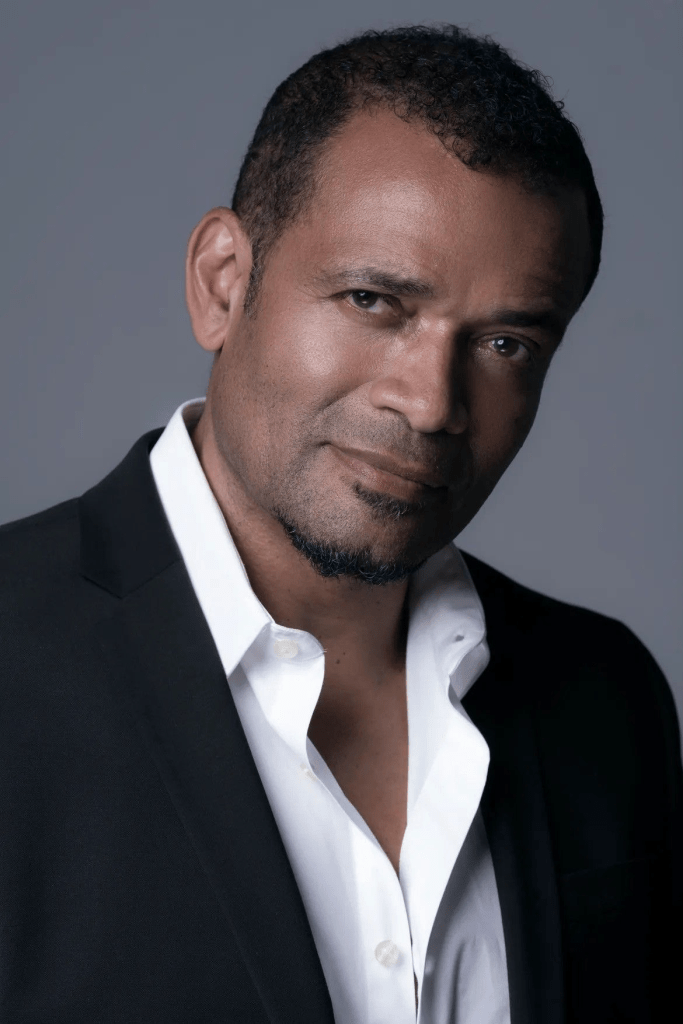

MM: The programme at BFI Southbank will definitely be engaging. We have a great line-up of entertaining movies. They’re campy. They’re poignant. They’re curious. They are movies that “flip the script” on who were the true western heroes. I’m particularly excited about our guests. Chief among them will be Mario Van Peebles.

ALT: Mario Van Peebles is part of the programme what do you think he adds to the programme?

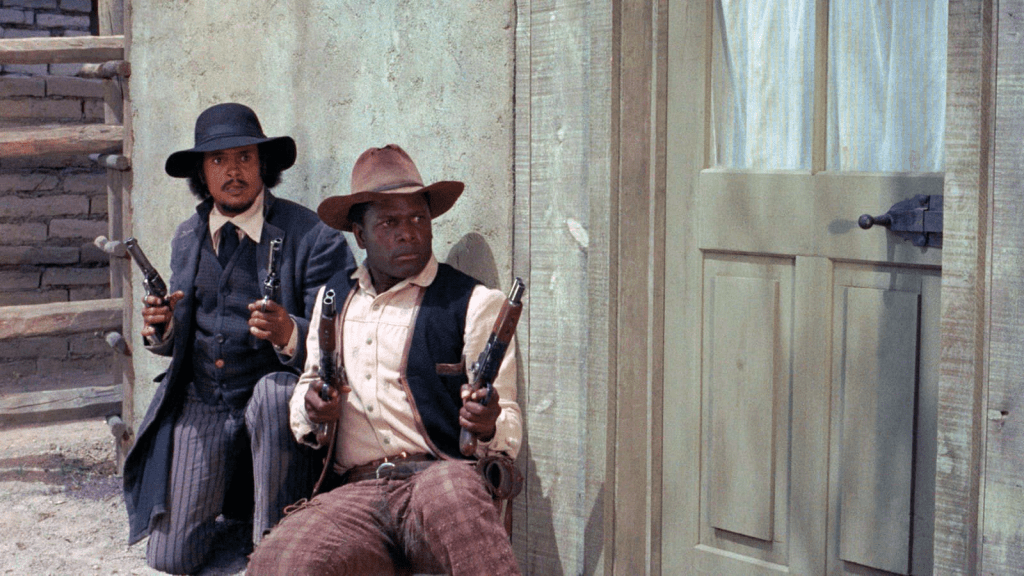

MM: Mario is so cool. He’s very talented. He adds a unique dimension to the entire program. First, his films are entertaining because he understands moviemaking. It’s in his blood. Secondly, he’s a touchstone figure. He’s a writer-actor-director who has successfully contemporized the western genre. Take Posse (1993) as a prime example. And he’s uniquely gifted at helping audiences understand why African American directors use the western as a tableau through which to explore contemporary themes.

ALT: What stories of Black Rodeos’ do you think we should know that should be more widely depicted, that many don’t know?

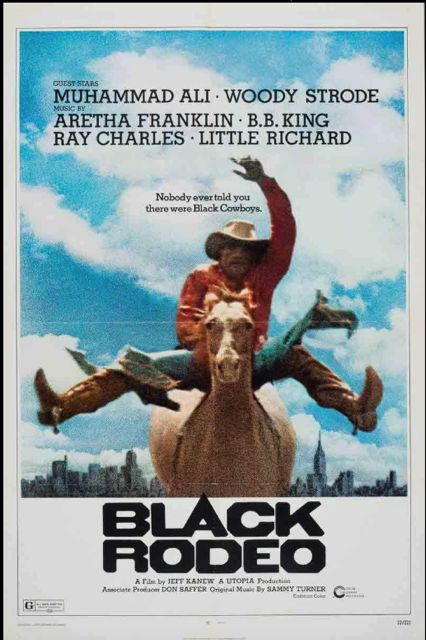

MM: Black Rodeo is a wonderful documentary by Jeff Kanew that was made in the 1970s. My book derives its title from Kanew‘s documentary. I would love for audiences to know this film. It features one of the first African American traveling rodeos. Black western cultural idioms have been in existence for a long time and have been celebrated for very long time.

ALT: Tell us about some of the actors of that genre that viewers might not know?

MM: Woody Strode is one actor that audiences may not know. He was a prolific actor in the 50s and 60s and 70s. He worked in film and television into the 1980s. He also appears Mario Van Peebles’ Posse. Strode, worked with John Ford in major films, including Sergeant Routledge, which is part of our BFI season program. Strode was also in Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). Other actors include Sidney Poitier, Jim Brown, and Fred Williamson. There were women in these westerns too. Ruby Dee, Julie Robinson Belafonte and Vonetta McGee.

ALT: Talk on Jim Brown’s and Poitier’s contributions are figures in the genre?

MM: Sidney Poitier and Jim Brown each made unique contributions to the personification of the western hero and to the western genre. Sidney Poitier always portrayed urbane, sophisticated gentleman – even when he was playing a rugged cowboy. There was an air of refinement about him. He portrayed an upstanding man with a strong, moral compass. That was an important component of early western hero figures.

Think back to Gary Cooper in High Noon (1952). Conversely, Jim Brown inserted a more viral or masculine energy into the black western hero / cowboy trope. Brown was a former football-player-turned-movie star, which is something I discuss in my book. There were a few of these men who left football for film. Nevertheless, Jim Brown appealed to younger audiences eager for athletically chiselled, super-macho, sex symbols who were physical with women. Jim Brown and Fred Williamson filled this niche in ways Poitier was disallowed. In some ways, Poitier and Brown contradicted and complemented one another as cinematic icons. Whereas Poitier’s star persona came to fruition in the 1950s and 60s, Jim Brown’s emerged in the mid-60s after Poitier had already laid some groundwork.

Black Rodeo: A History of the African American Western takes place at BFI Southbank from 1 February – 18 March, with the event Introducing Black Rodeo on 10 February