From the Navy to the film industry is not the most obvious route but cinematographer and colourist Jia Lang found his time in the Navy built his mental resilience and physical endurance. Working with some of the film industries notable talents from his short film Time Won’t Heal which was executive produced by Joy Gharoro-Akpojotor who runs Joi Productions and KOKO being produced by Jonathan Caicedo-Galindo who produced Sticks of Fury, and who produced Blue Story (2019) served as a kick-start to Lang’s career.

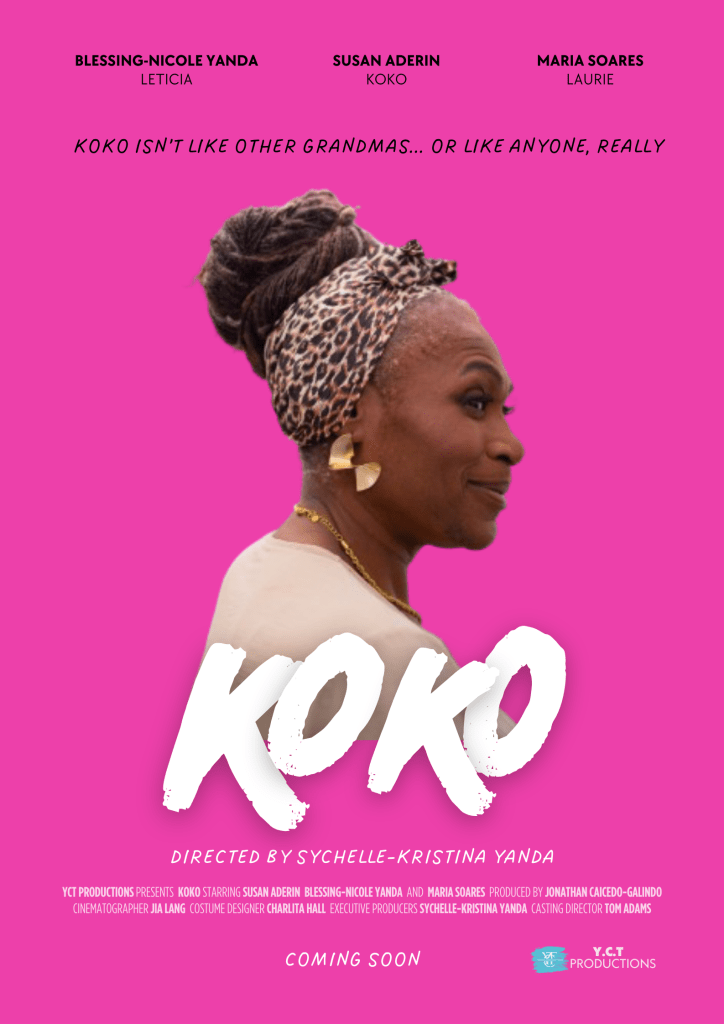

KOKO, Lang’s second short film as a DOP, was supported by the Phoebe Frances Brown Film Fund, the fund is run by Mister Tibbs for emerging female talent in the comedy genre. 2023, was the first year running the fund, in which they awarded Sychelle Kristina Yanda £1000 to support the film production of KOKO, the film was also screened at Close Up Cinema in London.

His music video Run, which was shot and colour-graded for Blessing Nicole Yanda, had its world premiere in May 2024 at the Oscar Qualifying Atlanta Film Festival and screened at the BIFA Qualifying Sunderland Shorts Film Festival the same month. He may be newish to the industry but his talent is not going unnoticed. Lang talks to ALT A about “cinematography”, being “one of the best tranquilizers for PTSD” and not “experiencing film the way westerners did”. It was not until he came to the UK at 37 that he realised “cinematography could be a career”.

What was it like working in the Navy?

Working in the Navy broadened the boundaries of my inner world, both mentally and physically, in ways I hadn’t anticipated.

During my time in the Navy, I learned that humans can go without sleep for seven days and nights, perform endless tasks, and overcome obstacles even in extreme conditions—without sufficient water or food—while still managing to shout political slogans.

Your sense of elitism and even your self-respect as a human being can be completely shattered during ‘Hell Week’ or ‘Hunter Boot Camp’.

Some Navy Marines even escape these extreme conditions – lack of food and water – by breaking into villagers’ homes to “loot”. The discussion that arises from this is, when death feels imminent, can law and ethics be disregarded?

And humanitarian disasters like this, intentionally created as part of war training, push you to the point of redefining your understanding of honour/responsibility/national interest.

The punishment for anyone who has broken into a villager’s home can be no sleep for up to 7 to 14 consecutive days, having to carry various strange heavy objects and make various funny movements, even if hallucinations appear and they start to become hysterical, they are not allowed to stop.

That experience shaped my perspective. I’ve become less prone to anger and more understanding toward people who, to me, are what I’d call linear beings. In fact, I find that war strategies and career strategies are strikingly similar. War requires a non-linear way of thinking, while many well-adjusted civilians tend to operate in more binary and linear ways, perhaps making them more predictable. A Navy Marine, on the other hand, learns to adapt to all kinds of situations.

To further elaborate, soldiers are the last line of defense for their country. There’s no way out—you can’t just say, “this isn’t our responsibility” and pass things to another department. In practice, you’re often faced with situations where you receive more than ten orders at once, all requiring immediate action. No matter how hard you try, there will always be tasks you can’t complete, and the punishment for that is severe.

Being punished becomes part of daily life in war training. The hot topic of discussion is often about today’s punishment not being as harsh as yesterday’s because we only failed to complete three tasks. This gave me better multitasking skills and a more adaptable mindset than most civilians. I actually enjoy folding multiple projects together and figuring out how to get them all done within the same time slot.

So when someone tells me, “Today, you just need to complete one task and then you can rest,” I instinctively know there are likely to be multiple hidden pitfalls. Linearity—only doing one thing at a time—just doesn’t seem realistic to me anymore, and it’s hard for me to accept.

..and how did you get from the Navy to cinematography?

Cinematography, for me, is one of the best tranquilizers for PTSD. It transforms into a spiritual experience. When you’re watching everything unfold through the DOP monitor, the world goes quiet. No one’s shouting at you, no assembly whistle is blaring, no tear gas is being thrown into your tent. All you have to do is let everything happen in front of you, in a certain rhythm.

After my Navy experience, my family had to endure some of my antisocial behavior. So it’s been a positive shift for both my family and civilian society that I’ve found this incredible outlet. Our army veterans, as a whole, aren’t well taken care of, so I’m grateful I was able to overcome such a major transition and adapt to this new life in the UK.

Growing up, what were your cinematic experiences?

Growing up, I didn’t experience movies the way many Westerners might have. I originally came from a region deeply rooted in agricultural civilization, where the government and associated industrial enterprises held a monopoly over the local culture. My time in the Navy, however, shaped my storytelling ability as a cinematographer. What I’m about to say might seem a bit unusual, but doing all sorts of tidy-up work in the Navy was a formative experience. It not only instilled discipline but also shaped my perception of aesthetics as a filmmaker.

The Navy’s constant requirement of discipline, precision, and activity left little room for rest, and I believe the images I create in a cinematic sense reflect my desire for more poetry in life. While representation through heritage is important, I hope people see me for my artistic voice, not just my identity.

Are they any filmmakers that you think influence your style?

I personally didn’t realize that cinematography could be a career until I came to the UK at the age of 37. Before that, I had next to no exposure to filmmaking culture.

One of the great experiences that really influenced my style was an encounter with Sychelle-Kristina Yanda, the writer and director of my short film KOKO. The film is a British-Congolese comedy short. KOKO means grandma in Lingala, a Congolese dialect, and was written during a time when Sychelle was grieving the loss of her grandmother.

I met Sychelle, at the National Film and Television School in Beaconsfield back in 2021, when her family was looking for a photographer for her grandma’s funeral. We ended up having a long chat about career goals after the funeral and realized that our paths were somewhat aligned. I was a photographer wanting to shoot, and she wanted to write. We teamed up, started making music videos together, and eventually made our short film Time Won’t Heal at the beginning of 2023.

Tell us how you work as both colourist and cinematographer: how do the two go together?

I’m usually quite kind to people who may be more lineair and I’m always full of curiosity. My career as a colorist actually began with color grading music videos, where I worked as a DOP. From there, things gradually escalated to short films, and eventually to feature films. The color grading business, in turn, has supported my career as a cinematographer by giving me more access to the industry, and my journey has always been marked by constant breakthroughs.

What makes you good at your job?

To me, creativity and miracles happen when you embrace the non-linear, embrace the fact that not everyone is like you, and that they may need help in some areas of their lives. My cast and crew often didn’t come from the same cultural background as me, and this has helped me become globally competent. I opened myself up to the skills they brought, ones I didn’t have, and that made all the difference.

What are the challenges to short film making?

To enter the world of short filmmaking, I had to tap into my background as a Navy marine. I often throw myself into unfamiliar situations on purpose because I know this strengthens my ability to adapt. My time in the Navy gave me a strong instinct for reading body language, allowing me to react quickly.

Working in London can be quite challenging, as it’s a culture I don’t always fully understand. I try to read situations, environments, and discussions, and respond smartly, even when I don’t fully grasp what’s being said. Every moment feels like a sudden flashback to my Navy days—my heart pounding, praying things don’t get worse while I wait for a chance to take control. If your daily work makes no ripples in your spiritual world, then perhaps it’s just a job, not a career. That’s my motto.

Time Won’t Heal is shot beautifully what can you talk to on technique?

Sychelle-Kristina Yanda (Sky for short) came to me with this heartbreaking love story set in the 1980s. She wanted to bring the essence of Small Axe and other black-led productions into my cinematography, which she felt had a certain nuance.

Chris Hosker, our longtime gaffer, is very experienced in narrative filmmaking. He lit the cast and spaces using a mix of hard and diffused light, adding atmospheric haze to soften the image. Keeping on schedule was a challenge for us, but we made a few compromises with the lighting plan and tweaked the shoot schedule to help speed things along. The resulting image in the interior scenes, I hope, created a beautifully textured world that highlights the cast’s tender yet visceral performances.

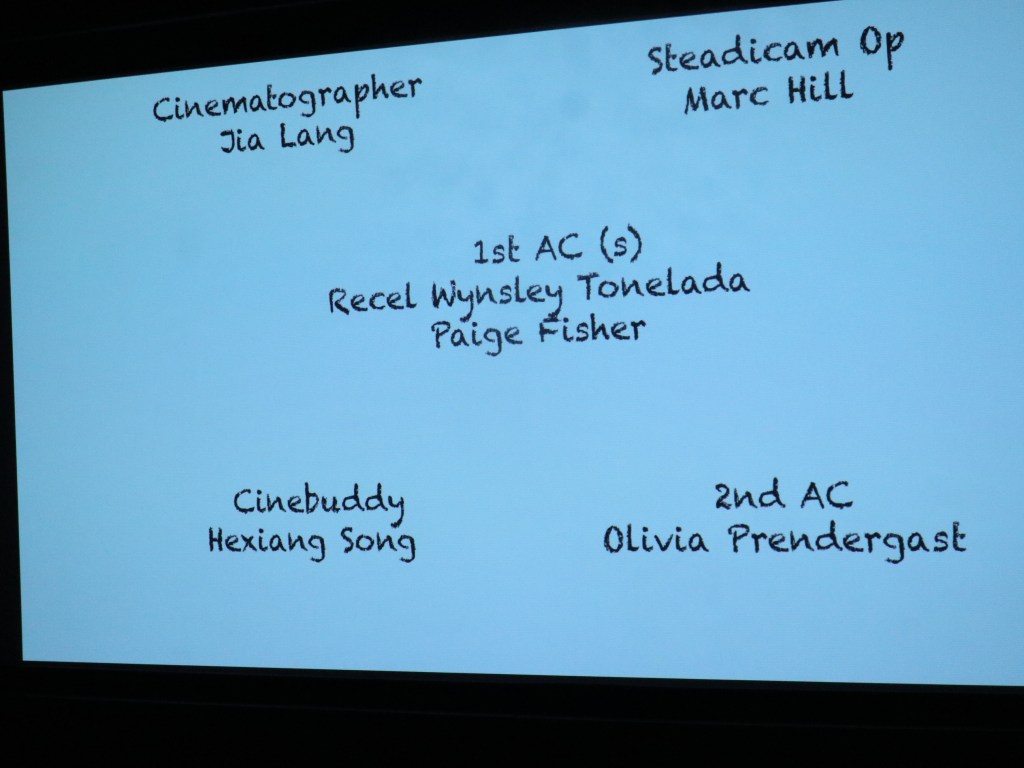

There was one intimate scene where, apart from the cast, it was just me and my focus puller, Recel Wynsley Tonelada. The rest of the crew were watching from the director’s monitor in the next room. Thankfully, I got the shot in one take. When Sky called “cut,” everyone rushed in to give me a high five. That was my first short film, and to this day, I’m still proud of it—a short film with a predominantly Black cast welcoming an Asian DOP to help tell their story.

Ben Thomas, my Steadicam operator on Time Won’t Heal, was also a marine. We were once on opposing sides, but later met in London and ended up collaborating on that short film.

What kind of stories are important to you?

I’m proud to say that I’ve shot almost all of Blessing-Nicole Yanda’s music videos and short films, and I’ve worked with most of her family. I’m helping Blessing make a name for herself in the rap genre, and we’re scheduled to shoot three music videos back-to-back in London over the next three weeks: Baby, Scrubs, and Malade.

A mystery collaborator will also be featured in the videos, adding an exciting element to the project. The upcoming music videos will showcase Blessing’s skills as a rapper, especially as she experiments with new musical styles. Being bilingual, she will highlight this ability in her music, hoping to expand her audience by connecting with listeners in both languages.

What advice would you give on short film making if you could share 3 tips.

To young cinematographers, I would say: start cutting your teeth on music videos and build your regular crew through those projects. Make friends in all kinds of communities. Become part of a space where so many gifted artists grow together. Be kind to critics, but avoid getting caught up in unconstructive discussions.