Oliver Enwonwu: A Continued Legacy

The use of the mask is wrongly understood by #Picasso. In the painting, he used it as a prop just as in museums in the West, where such African objects have been removed from their spiritual and religious context and placed in glass boxes. For the African, the mask is a transformative element and whoever adorns it is immediately transformed and elevated to a higher plane, representative of our ancestors. Oliver Enwonwu

“Oliver Enwonwu holds a master’s degree in visual arts with distinction from the University of Lagos, Nigeria. He comes from a long line of artists; his grandfather was a reputable traditional sculptor and his father Ben, widely celebrated as Africa’s pioneer modernist. In his work, Oliver Enwonwu elevates Black culture to challenge racial injustice and systemic racism by celebrating the cultural, political, and socio-economic achievements of Africans through an examination of African spirituality, Black identity and migration, contemporary African politics, Pan Africanism and the global Africa empowerment movement.

From 2009 to July 2021, Oliver served as the President of the Society of Nigerian Artists, established in 1963 as the umbrella professional body for all artists in Nigeria, which exists to engender the highest standards of practice and teaching of the visual arts in Nigeria.”

ALT’s Editor Joy Coker Founder, Entertainment/Travel Journalist caught up with the renowned artist Oliver Enwonwu ahead of “Oliver Enwonwu: A Continued Legacy”, the exhibition which opens at the Mall Galleries Tuesday 21st May – Saturday 1st June, 10am – 5pm.

The exhibition will feature paintings, drawings, and sculpture by Oliver Enwonwu, as well as works by his father, the acclaimed pioneer African modernist artist, Ben Enwonwu. In 1985, Mall Galleries was the stage for Ben Enwonwu’s last major international show, ‘Dance Theme.’ Additionally, 2024 marks the 30th anniversary of Ben’s death. As a respected member of The Royal Society of British Artists, this timely exhibition is a testament to his legacy.

ALT A REVIEW:

Thank you so much for talking to ALT A REVIEW in advance. So firstly— a little bit about your father the late great artist Ben Enwonwu, and I ask why do you think so many people were connected to your father’s works?

OE:

Thank you first of all for having me. It is my pleasure to be chatting with you on this occasion of the forthcoming joint exhibition with my father “A Continued Legacy”.

I think a lot of people including artists are drawn to him because before his appearance on the art scene in Nigeria and Africa, the art profession was one of ridicule. He gave it respectability through his many successes.

At the height of his fame, these successes were used to champion Black nationalist struggles all over the world. In his own country Nigeria, his many successes paved the way for our independence from colonial rule through his Pan Africanist views and his championing of the Negritude philosophy as chiefly espoused by the first president of Senegal, Leopold Senghor.

Indeed, my father created works that agitated for the emancipation of Black people and forced people all over the world to dismiss the stereotypes of negativity thrust on Blacks. Through his work and that of the other artists who followed him, Black people were judged on their merit and not by the texture of their hair, the colour of their eyes and the colour of their skin.

Also, one of his legacies is the forging of a new visual language for Nigerian art, which merges our best traditions and indigenous aesthetics together with Western techniques and modes of representation. His achievements were significant because it was important at that time for Africans all over the world and for African countries gaining independence then to form their own identity and begin the process of decolonisation. My father is very important because his art was used to foster that process.

In addition, when you revisit history, you see that some of his great public sculptures in Lagos, like “The Drummer”, which for many years was located on the façade of the telecommunications building and “Sango”, still installed at the Eko Distribution Company headquarters — then known as the Electricity Board— became national symbols for telecommunications and electrical power supply respectively. They’ve since been entrenched into our collective national consciousness— a feat no other Nigerian artist till date has accomplished.

Here is an Igbo man from Onitsha who through his works like “Tutu”, a portrait of a Yoruba princess— was able to bring Nigerians of various ethnic groups together, foster peaceful coexistence and encourage better understanding between them. Indeed, his work transcended ethnic and tribal boundaries as it is nationalist and Pan-Africanist.

Today, many artists have defined their practice against his framework. Incidentally, he was Nigeria’s first professor of art. And of course, you can imagine the successive generations that have learned from him. So little wonder why people are still drawn to his art more than 30 years after he passed away. Indeed, people still celebrate and hail him Africa’s most influential artist of the 20th century.

ALT A REVIEW :

Of course. Let’s talk about you and how you came into art; obviously I know you studied biochemistry and geophysics. What was it growing up that influenced you so much? Obviously, you must have been around your father and all the things he was creating so at what point did you think, oh my gosh, I can do this?

OE:

Well, he greatly encouraged me as a boy. It was just like you said, growing up smelling paints and being surrounded by great art including paintings. I literally watched my father create works, many of them virtually appearing from the chunks of wood he sculpted . However, I wanted to be my own man and do my own thing. Because I excelled at school in the sciences. I wanted to be a scientist and felt that my art could always occupy a secondary role.

It’s also quite a difficult thing growing up under such a looming figure that you discover you don’t want to compete but would rather make your own mark. I went on to study biochemistry first, then geophysics. All the while, I continued to paint. As I grew older, my art became more of a pull, and I see it as a calling.

I was increasingly drawn to my art and the rest is history. One day, I woke up and decided it is where I ought to be. I followed suit and maybe that’s what fate is all about. I enjoy my art tremendously. I never enjoyed my sojourn in the sciences as much as I’m enjoying my art. Forme, it is something of a homecoming and I feel that I’m in my natural habitat.

ALT A REVIEW :

Both you and your father put out important messages in your work. What would you say you have in common with the message in your works? What are the parallels and maybe the differences in your message?

OE:

I’d say that what we have in common is our use of the female form and the woman as a motif. We both see women as nurturers and incubators that multiply in good measure whatever is vested in them. But there are many differences from technique to even the message because I live in different times, and so interpret what is going on around me… likewise, my father dealt with issues that were present in his time.

For instance, my work is more politically conscious. Some of my paintings deal with the marginalisation of the Igbo as evident in the last general elections in Nigeria when Igbos were asked to return to their respective bases to vote. This ethnic injustice during the elections happened in my own time.

Our techniques are also different and so are the colours and forms. I’m more of a realistic, figurative painter while his works are heavily stylised through the elongation of forms. This is not really my approach. My layering of the paint is different too. So, our forthcoming exhibition is an interesting conversation where one would see the clear difference in styles.

ALT A REVIEW :

Can I ask you to maybe talk a bit on the title “A Continued Legacy”, which almost is self-explanatory?

OE:

Yes, the Mall Galleries is the venue of my father’s last major retrospective in Europe. The exhibition is also an occasion to mark the 30th anniversary of his passing. I felt it would be important to hold this exhibition at the same place he staged his last to add more interest and underscore the importance of that continued legacy.

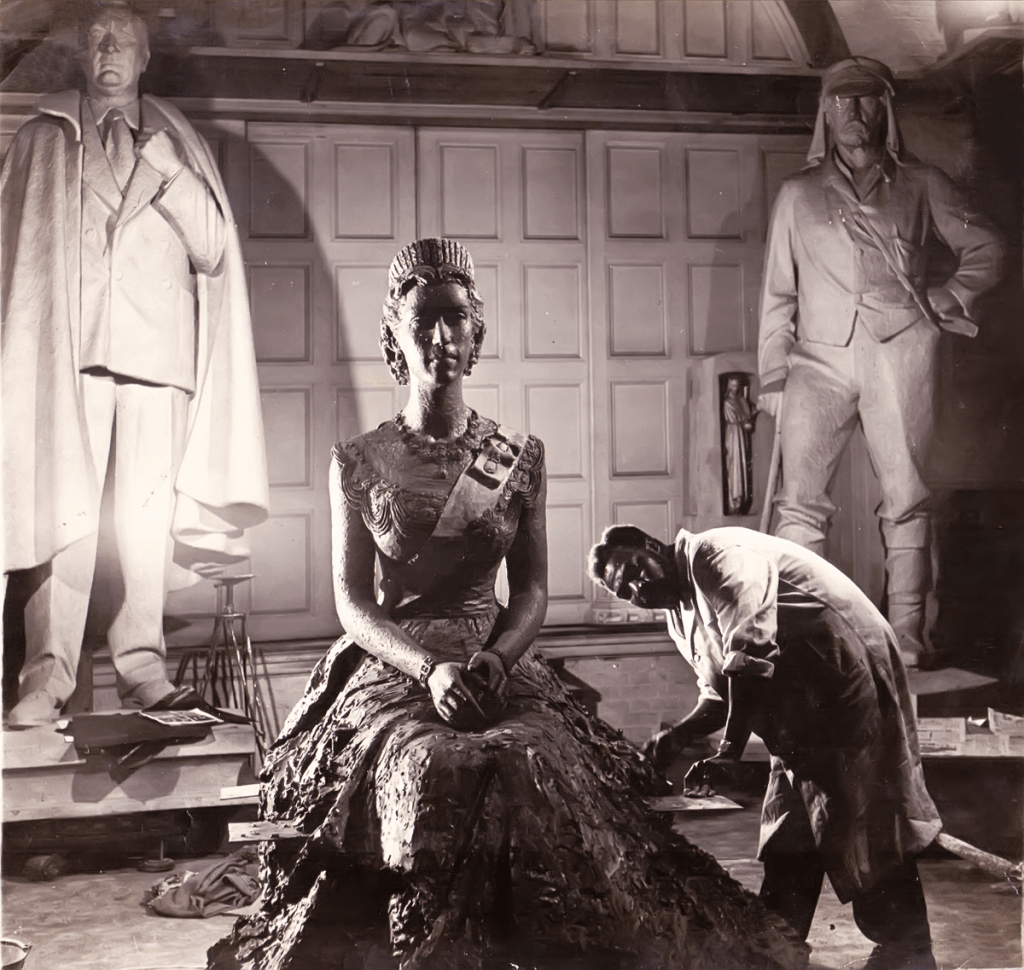

It’s also important for me to highlight the fact I come from a line of artists and my father is just a second generation one as his own father was also an artist. The legacy actually begins with my grandfather, a traditional sculptor of repute and then continues to my father who is celebrated as Africa’s pioneer modernist artist, and then on to me. The title and the reasoning behind it illuminate this history.

ALT A REVIEW :

One of the many new paintings that you have done for this exhibition is called “Were God to be a Woman”, can you talk on this works?

OE:

Certainly. “Were God to be a Woman” is my response to “Demoiselles d’Avignon”, one of Picasso’s most famous pieces, in which many of us feel that African women were denigrated. In addition, it wasn’t until much later that Picasso himself gave a little bit of credit though not in good measure to the geometric forms and shapes of African art, which gave birth to modern art.

And so, it was important for me to seize the narrative and challenge what he did. It was also important because those women in Picasso’s painting were prostitutes. I wanted to give the African woman dignity and self- respect. My work is all about celebrating Black excellence. In my painting, the gazes are confident and focused. There is also a sense of pride. I’ve expressed the beauty of the Black African skin too.

The use of the mask is wrongly understood by Picasso. In the painting, he used it as a prop just as in museums in the West, where such African objects have been removed from their spiritual and religious context and placed in glass boxes.

For the African, the mask is a transformative element and whoever adorns it is immediately transformed and elevated to a higher plane, representative of our ancestors. I make sure that this is communicated in my work because the women should be respected. When the women in my painting adorn a mask, it’s not for aesthetic purposes but it’s an elevation and that underscores my thrust which of course, challenges the denigration in Picasso’s work.

ALT A REVIEW :

Alongside your new paintings in this exhibition, can you tell us a bit of what we can expect from the works that your father has in the exhibition?

OE:

Well, there are a few examples. One of the highlights is a conversation around “Tutu.” It is one of my father’s most famous works. There are three iterations— all portraits of a princess of Ile- Ife. Incidentally, I have also painted a series of four portraits of Tutu’s niece, Ronke— also an Ile-Ife princess. Some of these works will be showcased so that people can understand the conversation— which of course highlights the theme— “ A Continued Legacy — across generations and between the artists and sitters that share filial relations.

Archival photographs will also feature in the exhibition. They document important moments in my father’s life. I ‘reenact’ them several years later even though they were unplanned. I think that it’ll be interesting for viewers to see that sometimes history is repeated in many ways.

ALT A REVIEW:

How does it feel to have this moment; how important is it to you?

OE:

It’s very important in many ways. To go forward, you need to understand your past and where you’re coming from. Part of whom I am is my legacy and my history. The same goes for Nigeria, Nigerians, and Africans all over the world. I think we are experiencing a loss of self and of history.

This is evident in our schools where our history and even languages may no longer be taught. This is because in many ways, Western education is valued above ours; we’re taught a different kind of history that doesn’t necessarily celebrate the best of what we have.

This is injurious and has given us a sense of loss, especially when you also consider that many of our traditions were oral and not documented. Today, many Africans cannot speak their indigenous language and do not remember the last time they went to their hometown. Having this exhibition with my father brings me closer to my roots. In sum, through my work, I interpret indigenous traditions in a contemporary manner to solve or respond to pertinent issues affecting Africa and the rest of the world.

ALT A REVIEW :

And you were also president of The Society of Nigerian Artists?

OE:

It was for 11 years, from 2009 to about 2021.

ALT A REVIEW :

Okay. So just to ask where we are now because we’re seeing in Africa that the whole landscape is kind of accelerating? We all know that indigenous people have always been creative art from time immemorial, but now on the international landscape there’s a big, massive movement in terms of the appreciation of African art.

Some say it looks a lot bigger than it actually is. So, what do you think about where we are now in terms of competing, art sales and exhibition spaces? Do you think we are in a much better place? Do you think there’s a lot more to do? Do you think some of is superficial? What’s your view?

OE:

Very good questions, which would like to approach from several points. First of all, I’d say there has been a lot of improvement but we’re not really where we ought to be. For a long time, we haven’t been given our due; modern art was championed as a creation of the West without giving credit to the geometric forms of African art that birthed modern art in the first place.

Here, we had artists like Picasso borrow so much from African art without due acknowledgment . Modern art itself, as part of the history of Western art, is documented from a European viewpoint. Africans are underrepresented in the Western canon of art and when they feature, are depicted in subservient fashion as servants and not in the upper echelons of society. This non- inclusion from the start has been disadvantageous to the development of our art.

Today, our art survives because of our immense creativity evolving from our several experiences. For example , the advent of Christianity, which has impacted on our art. We have also had Western patrons contribute to our artistic development. We have also experienced technological and industrial growth , as well as colonialism. All of these phenomena have but enriched our art.

This is why you see the explosion styles and different techniques especially because we still retain traces of our traditional past. Today’s artists produce hybrid forms of art that embrace the effect of these events.

This is what makes our art so interesting. I also think that because of this exciting development, the West is attracted to our art. International galleries are still coming in, though from very cheap price points. Ultimately, this development doesn’t augur well for our art development.

In addition, you cannot sustain that explosion of creativity if you don’t have the infrastructure. For example , how many galleries are working at an optimum professional level in Lagos?

How many auction houses do we have? Do we have specialised storage and what are the publishing houses doing; in addition to printing books, do they have the capacity to distribute them all over the world?

It’s one thing to print books and another to know where these books are read so they can have great impact on global art discourse. In summary, do we have that ecosystem to sustain our growth? If not, we will have all the creative talent, but which isn’t well managed and harnessed. On the international market, we now witness, for instance, our art recording huge amounts at auction.

This is a welcome development; however, you can’t compare prices fetched at auctions for my father and Picasso. It’s an anomaly, especially when you consider that as early as 1946, both men were showing side by side in the same exhibition’s spaces. What happened in terms of the price points?

One artist has gone on to command incredible amounts on the international market. This anomaly may be due to the absence of a well-developed local ecosystem to support growth. With the advent of the internet, more people are seeing our work, but we need government support to build the right infrastructure. Of course, government cannot be a player but should create an enabling environment.

LOOKING FOR A JOB IN THE CREATIVE INDUSTRIES: ACCESS THOUSANDS OF JOBS

Furthermore, why can’t I take a highly valued artwork to a local bank in Nigeria as collateral to secure a loan? This is another aspect of development. What about the art insurance companies ; how many of them are there? What about those who provide art valuation services? So, you can see we do not have a proper system and that has affected the sustainable growth of our art sector. So yes, we have great creativity for many of the reasons I’ve mentioned but we don’t have the infrastructure to sustain it. We are not yet on the level we are supposed to be on, and that is for me a problem.

ALT A REVIEW :

Sorry, so you’re saying really that the answer lies within Africa to build up its own infrastructure and make these things happen themselves? So, what would you say for the other day when I was at Sotheby’s and saw one of your father’s works up for sale? I know they’ve been selling them somewhere in the region of 1 million pounds and more. Is that not something you think is good?

OE:

Well, it’s a good thing but we are not yet where we are supposed to be. Modernity didn’t occur only in the West. African artists engaged modernity on their own terms. As I mentioned earlier, we haven’t been given due credit but placed on the peripheries. This is why it was difficult to break onto the global stage. And so, while some of our artists have achieved individual global recognition, their prices often still pale in comparison to those of their international peers. The same can be said of African art a collective. When you consider Picassos sold for 80 million pounds, it means the West is doing 80 times better.

ALT A REVIEW:

As an artist, is AI something you fear, or do you think it’s innovative?

OE:

Well, it’s innovative but just like any new thing, it has advantages and disadvantages. It’s a new phenomenon and we do not know fully where it’s headed. I believe technology is good if well controlled. However, it shouldn’t replace artists but can be used to complement and perhaps scale up production. Take several examples from other disciplines like medicine, where good use of technology can help with pin- point surgery and the substitution of cancerous tissue. In contrast, it’s unethical to clone a human being. Another example could lie in some people reading their Kindles and online. There are others still, who want the feel of printed books and collectors or who collect old manuscripts.

One form cannot substitute the other, but they can act in complement. Technology can be good, but it depends largely on its ethical use. For example, AI can be used to enhance an artist’s creativity. You can even use AI to build provenance for an artwork. Artists can also generate models. Those who work with photographs may use AI to enhance colour and their prints. Is it going to completely erase what the need for artists? No, because there are collectors that want to feel a connection to an artwork created with a heart, mind, and hand and not to software or a machine.

The market is expanding, and tastes are changing. My specialty is fine art, which is fully human generated. However, it doesn’t stop me from appreciating artists who work with AI.

ALT A REVIEW :

What do you say to anyone about attending “A Continued Legacy”, why should they see this exhibition?

OE:

If you are studying African art, seeking to understand your existence and your people’s development; where they come from and how they’re using their own indigenous knowledge to understand their existence while dealing with pertinent issues affecting Africa and the rest of the world, then the exhibition could be a draw. The exhibition is also for those who want to see Africa at her finest and learn more about her history, through the lens and experiences of two successive generations of African artists. Significantly, the exhibition illuminates how a legacy has evolved from one generation to the next. In addition, viewers will gain insight into how Africans can challenge negative stereotypes of the continent and tell their own stories.

ALT A REVIEW :

Where do you call home?

OE:

I live between Kent in the UK and Lagos.

When: Tuesday 21st May – Saturday 1st June

Where: Mall Galleries The Mall, St. James’s, London SW1Y 5AS

You might also like: Chelsea Flower Show: Saatchi Gallery commissions Zak Ové for annual Garden