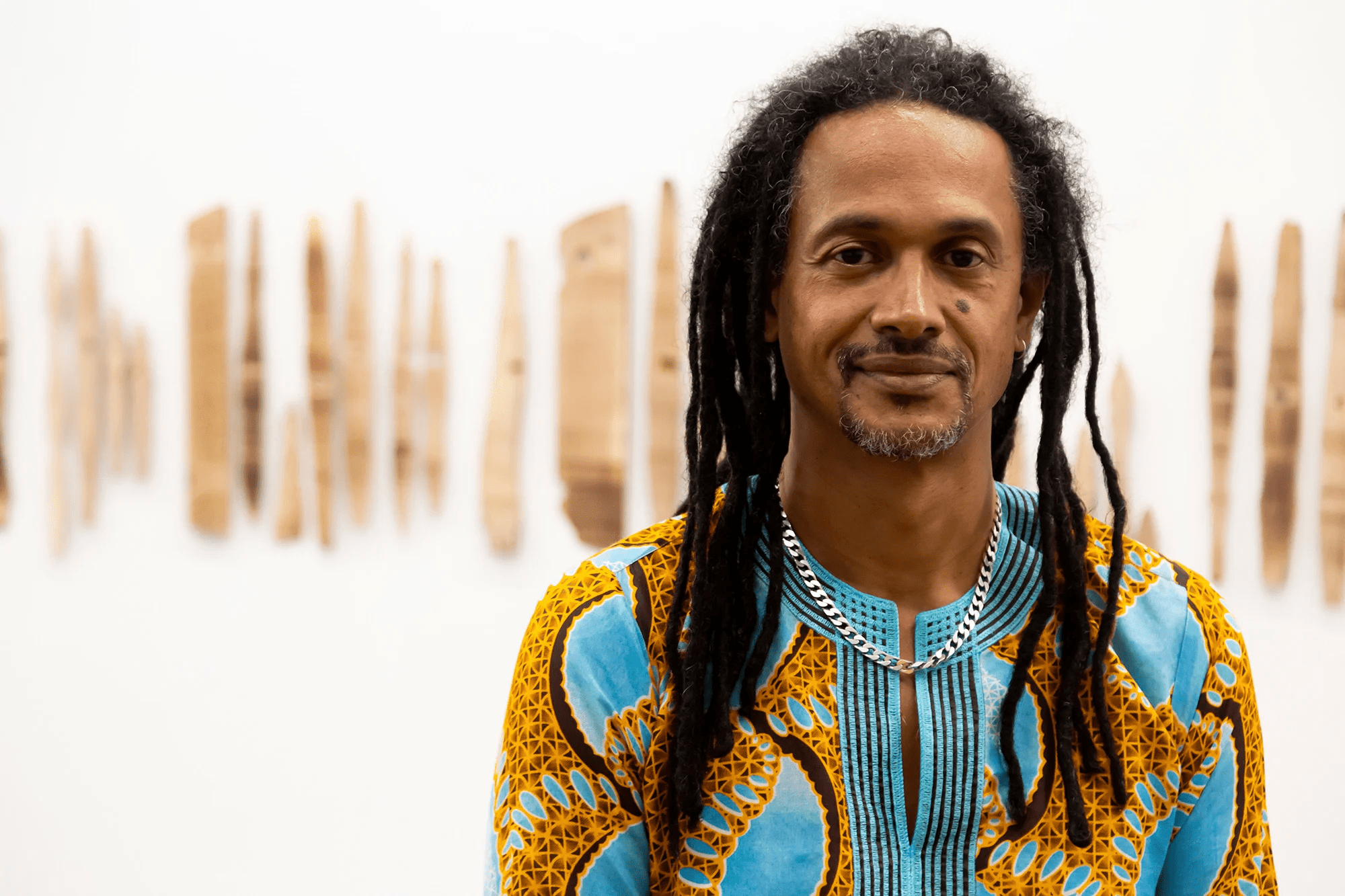

Artist Interview Kimathi Donkor

“I think I quite like the idea of being able to communicate with people but not necessarily being there. So less performative.” Kimathi Donkor

Kimathi Donkor is among 22 artists whose works appear in the 2024, The Time Is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure group exhibition running at the newly opened National Portrait Gallery in London. Born in Bournemouth, England, Donkor is of Ghanaian, Anglo-Jewish and Jamaican family heritage, and as a child lived in rural Zambia and the English west country. He lives and works in London, where he is the Reader in Contemporary Painting and Black Art at the University of the Arts, London.

“A major study of the Black figure – and its representation in contemporary art”

The exhibition, The Time Is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure curated by writer Ekow Eshun, showcases the work of contemporary artists from the African diaspora, including Michael Armitage, Lubaina Himid, Kerry James Marshall, Toyin Ojih Odutola and Amy Sherald, and highlights the use of figures to illuminate the richness and complexity of Black life. As well as surveying the presence of the Black figure in Western art history, we examine its absence – and the story of representation told through these works, as well as the social, psychological and cultural contexts in which they were produced.

The exhibition features the work of leading artists including Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Hurvin Anderson, Michael Armitage, Jordan Casteel, Noah Davis, Godfried Donkor, Kimathi Donkor, Denzil Forrester, Lubaina Himid, Claudette Johnson, Titus Kaphar, Kerry James Marshall, Wangechi Mutu, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Chris Ofili, Jennifer Packer, Nathaniel Mary Quinn, Thomas J Price, Amy Sherald, Lorna Simpson, Henry Taylor and Barbara Walker. The Time is Always Now runs until 19th May 2024.

Art by Kimathi Donkor is held in public and private collections including at The British Museum, the Sharjah Art Foundation, the Wolverhampton Art Gallery, the International Slavery Museum, the collection of CCH Pounder, the University of Greenwich and the Sindika Dokolo Foundation. He is represented by Niru Ratnam Gallery in London.

ALT A:

Can you tell us a little bit about your practice and what inspired you to take this journey into art?

Kimathi D:

I am predominantly a painter, but I also make other forms of works, there is quite a lot of drawing involved in my practice and I’ve made videos and installation. But mostly I work in the field of painting. My inspiration. That’s such a good question. I suppose it’s a mixture of things. It’s partly to do with being inspired by art and artists that I love and or admire or sometimes I am irritated by art that gets on my nerves. And I suppose the other thing for me is wanting to communicate to people through that particular method. I think I quite like the idea of being able to communicate with people but not necessarily being there. So less performative.

I am really interested in philosophical questions about culture, history, identity. I’m a person who you can say has a complex family heritage and I move between different sorts of cultural traditions. And I suppose I like to take it all in. So, I’m interested in certain African art traditions like the Ife portrait sculptures from Nigeria. And I’m also interested in the European painting tradition and literature. I’m constantly being interested by stuff, but certain things really do grab my attention. And I’m particularly interested in what you could call black or African history.

And especially I suppose I’m drawn to, when I think about historical characters, I’m drawn to moments of crisis, I suppose you could say heroism. I’m drawn to moments when people faced with great crisis or historical crises, how they elevate themselves and their communities, their families out of that situation. So figures like Harriet Tubman and Queen Nanny of the Maroons (I think will be talking about in this interview,) really inspirational characters for me because of the way they confronted terrible circumstances such as colonialism and slavery. So I think that is pretty kind of weaves it all together, doesn’t it?

ALT A:

Do you think as an artist whose works mark social political subjects or make social political commentary that automatically you become an activist? Or do you think that’s a subconscious choice you make?

Kimathi D:

So I suppose that’s a really interesting distinction, the word activist, a bit like the word artist, and in fact almost any word, it could become more and more expansive, can’t it, and start to mean anything. I think I have a particular take on those two phenomena activist and artists. Because when I first started art school, when I was a teenager back in the 1980s, I was literally an activist as well as an artist. And by literally, I mean that I would undertake activities in the community that were designed to encourage participation in politics.

And that was quite broad ranging. I was probably what some people might have the called the renter crowd. If it was anything that was bad, I always wanted to protest against it. But particularly when I started living in South London, and I suppose as much as anything, partly through my earlier experiences of living in England and the racism that I experienced as a child, but also through the continued expression of that racism, which I experienced when I moved to London, I became quite deeply involved in black community activism, particularly starting in 1985 when we had this crisis around the shooting of Cherry Groce in Brixton by police and the death of Cynthia Jarrett and Keith Blakelock, well, she died in a police raid and he died in the sort of conflict which came about immediately afterwards.

And so, in the aftermath of those events, and both of which I kind of knew the locality quite well, not super well, but I’d started to make connections in those localities in Brixton where I was living.

And in Tottenham where I had friends, I was drawn into, should I say drawn into, I think I was very keen to get involved in the sort of campaigns for justice and my art came with me. So, I would do illustrations for flyers and posters in the days when we used to make things it, I would distribute these materials people as part of a collective or group set of collectives with other members of the community. So, I wanted to put my limited artistic talents to use in that sense.

So, if a leaflet needed a little sort of power fist, then I would be the person that would draw it, that kind of stuff. And so in that sense, being an artist and being an activist sort of became merged in my life and that continued. But when I left art school, definitely the artistic side of it dropped off. I mean, I carried on doing, being involved in graphics and design for the groups I was working with. But I stopped participating in the gallery economy of art exhibitions and stuff like that more or less in around about 1990.

And so for that decade, the nineties, I was pretty much just an activist and not really much of an artist at all. And then around about the mid-nineties I thought, well actually I am an artist, but nothing’s happening. I’m not doing it. I’m not making much work. I kind of decided that I would actually switch and sort of focus more on the artistic side.

But what was interesting was that all of the stuff that I’d learned in my activist days about political history and identity culture community had become really fused, I mean it was, for example, in my degree show at Goldsmith, I did drawings about the crisis in Brixton and Tottenham in ‘85. That was what I submitted for my examination.

And so, when I reignited my art career in the early 2000’s, it was definitely with the idea that all of this activism that I’ve been involved in, I’ve been teaching black history classes and running black history and black culture classes and adult education in the voluntary sector capacity. And yes I merged them. So to finally answer your question, . So to kind of conclude, what I’d say is that, you can actually be an activist artist, which I wasn’t quite so convinced of before.

I think when I was younger I thought there was more of a distinction between the two. But now I would say that I can see the gallery space and the other spaces as spaces for being able to communicate to people, not necessarily in the manner of protest, but sometimes in a manner of protest, but also in a manner of critique and celebration.

So I can see the sort of gallery, the mural, the public art space I feel much more comfortable with it as a place of community engagement. I’m not sure yet if it goes as far as describing as activist, but it certainly could be on the spectrum if you like.

ALT A:

Looking at your earlier works when you addressed death police custody, with images such as of Cynthia Jarrett as you mentioned. I think you’ve explained why you thought it was important to, or maybe if you want to elaborate, why you thought important to put those pieces out there?

Kimathi D:

That’s really interesting as well. So if you, go back to 1980s, when I first started working with those stories, with those narratives, I mean then it was really pertinent to me because I was spending a lot of my time being an activist around these kind of issues.

Campaigning around, I became involved in a lot of those campaigns for justice around the shooting of Cherry Groce and other police custody questions.

And so those works which I created then were partly autobiographical in the sense they weren’t about me, but they reflected what were my concerns, what was on my mind all the time. I was traveling around the country giving talks and trying to mobilize people and stuff like that.

As a student, when I reapproached these issues back in the 2000’s, a decade and a half later, still coming up in my work, I think it was from a completely different perspective then, it was more about memory and thinking and thinking about a memorial and reflection and thinking about how at the stage, for example, in the early two thousands when I painted pictures about Cherry, Groce, Cynthia Jarrett, Keith Blakelock, it was about thinking about the way that I felt that these things which had been so big in my own life, they’d become forgotten almost, obviously not by the families of the people involved, where these kinds of things will be raw forever, but in the wider sense.

And I felt as well that kind of forgetting was impacting my daily life. And what I mean by that is, for example, my young nephews would tell me about their harassment by the police and how they were being constantly stopped and searched. And I thought this is partly a kind of institutional, not racism, but institutional or a national forgetting, have we forgot where we’ve been? Do you know what I mean? Have we forgot that this type of discrimination, segregation just leads to more and more conflict and violence.

And there was a sense that nothing had been learned. And I suppose in that sense, the pictures were supposed to be, I don’t know, you could accuse me of being a didactic educational, they were like, look at this happened. And it’s as much a reflection on today, even though it might seem a little bit disjointed.

And then I suppose the other thing about that is why that work is important to me is because I also think that there has been, particularly in a certain type of western art, the sense that amongst many that art, that art especially couldn’t be concerned with these sort of, I suppose politics if you like, social questions, questions of injustice and equality and conflict and resolution that art had other concerns.

And this is kind of reflected in it, particularly even in the way that when I was school, in the way that it was taught that you had a ID was you’d be interested in colour in an abstract sense that in relation to abstract art, you know what I mean?

And we forget that actually colour has got a really important political and social question around racism. For example, colour around identity like flags. So there was this sort of tension in the art, in my experience of the art world between art, which seems engaged with the issues of the day and art, which sort of wishes to or thinks that it’s sort of disengaging, but perhaps might otherwise be thought of as being not so much disengaged, but you could even call it callous or unempathetic, I don’t know. So I suppose in that sense is not, the work isn’t so much just about thinking about questions of the community, questions of the collective questions of society, but also particularly about art, particularly about the gallery, what is an artist.

And it’s quite a dangerous path in a way because obviously artists can become propagandists and propagandists can do bad things if they work. So there’s that kind of danger, am I just becoming a propagandist and where might that lead? So yes, I think I’m interested in that element. And I think in a sense that is part, that’s something which, the other thing that happened in the 1980s was the emergence or the re-emergence of the Black Art Movement.

And many of these members I was sort of connected with and exhibited with at that time. And that was very much a socially engaged art movement. And that is it came from being fairly marginal at the time and slightly ridiculed or ignored, it’s become very central. And we see obviously with the show at National Portrait Gallery and also the current show at the Royal Academy and many other sort of exhibitions over the years, it’s that idea that artists are people who are engaged with the machinations of the world has become really quite much more central important. I don’t know if that answers anything.

ALT A:

It does. You mentioned colour and how it sits in this space. So let’s speak on the title of this exhibition. How do we reframe the Black figure? What does that mean to you?

Kimathi D:

Well, I have to say I had nothing to do with it with the titling of the exhibition. So that is the choice of the curator or the curators of Ekow and the National Portrait Gallery, portrait. But obviously I do recognize the relevance of that and can think about this question and certainly engage with it in my work.

I mean, obviously most of my work is figurative it, the sense that it’s about, it depicts people, places, things recognizably and situates them in relation to each other in the picture frame. I was sent a video the other day of this portrait which had emerged in the United States of this family portrait, which had included an enslaved figure, this young boy who sometime late 19th century had been painted out, but you could still see the sort of outline. And then the Metropolitan Museum acquired this painting after it had been restored.

And you could see this child with this white family. And that’s a really literal instance of reframing the black figure in the sense that the black figure had been removed from the frame of portraiture in this particular instance. And it has really appeared back into the frame.

And it’s about how that first depiction, what were they doing, putting the slave boy in there? What was the purpose of it? Why was he there with this family? Why did so many European, Western European painting, British paintings have pictures of enslaved people? What’s the message that’s been conveyed?

Why are they sometimes erased or forgotten or put into vaults and no one wants to talk about it. And then how do following the abolition of the legal abolition of slavery, the abolition of the formal abolition of slavery, the formal decolonization of the empires, how do we as black people, how do we interpret that work and how do we want to put ourselves, our families, our communities, into the realm of painting with the knowledge of that history? And so for me, particularly, I’m showing two paintings in the show one is a painting depicting Nanny of the Maroons.

And what I did for that, so Nanny of the Maroons for listeners or for readers who don’t know was during the 18th century, a Jamaican anti-colonial resistance fighter. So I don’t think we know much about her origins or even much about her to be honest, but we do know that she definitely existed that led that she commanded a community of resistance fighters who collectively across the whole of the Caribbean and much of South America were sometimes known as maroons.

And that she established them as a sort of a viable community, which was able to resist British military attempt to sort recapture, suppress, kill them. And at one stage she even managed to negotiate a kind of truce treaty with the British state, which basically enabled her and her community to live apart outside of the slave system with their own sub territory in Jamaica. I recently went to Jamaica and I walked back some $500 notes and they’ve got nanny a picture of Nanny of the Maroons on the 500 Jamaica dollar notes.

She was declared a national heroine after independence and because of her ability to resist and to lead. But despite the picture on the $500 Jamaican note, there are no, as far as we know, there are no contemporaneous pictures made of her at the time, no drawings, or paintings. So anything that we create that depicts her now has to be imaginary. And so I was working this process called Unmasking in Africana, where I would look at artworks which had a kind of connection to the slave system or to colonialism from the western European perspective, but which you couldn’t necessarily see that in the image.

The other thing about this process is it has to be contemporary with the black figure I’m working with. So at the same time as Nanny of the Maroons in the forest of Jamaica with her sort of muskets shooting at the British at the same time in England. So Joshua Reynolds was the great portraitist of the age in the sort of 18th century England who was painting aristocrats in what he called or what was called the “Grand Style”. And one of the aristocrats who he painted was this lady called Jane Fleming mezzotint portrait of Jane (Fleming……

Part 2 of this interview can read in the next edition of ALT A REVIEW

Find out more about the exhibition The Time is Always Now Here.

You might also like:Red Carpet Exclusive: Hugh Jackman attends Marvel Studios’ ‘Deadpool & Wolverine’ Battle-It-Out UK Fan Event & UK Press conference